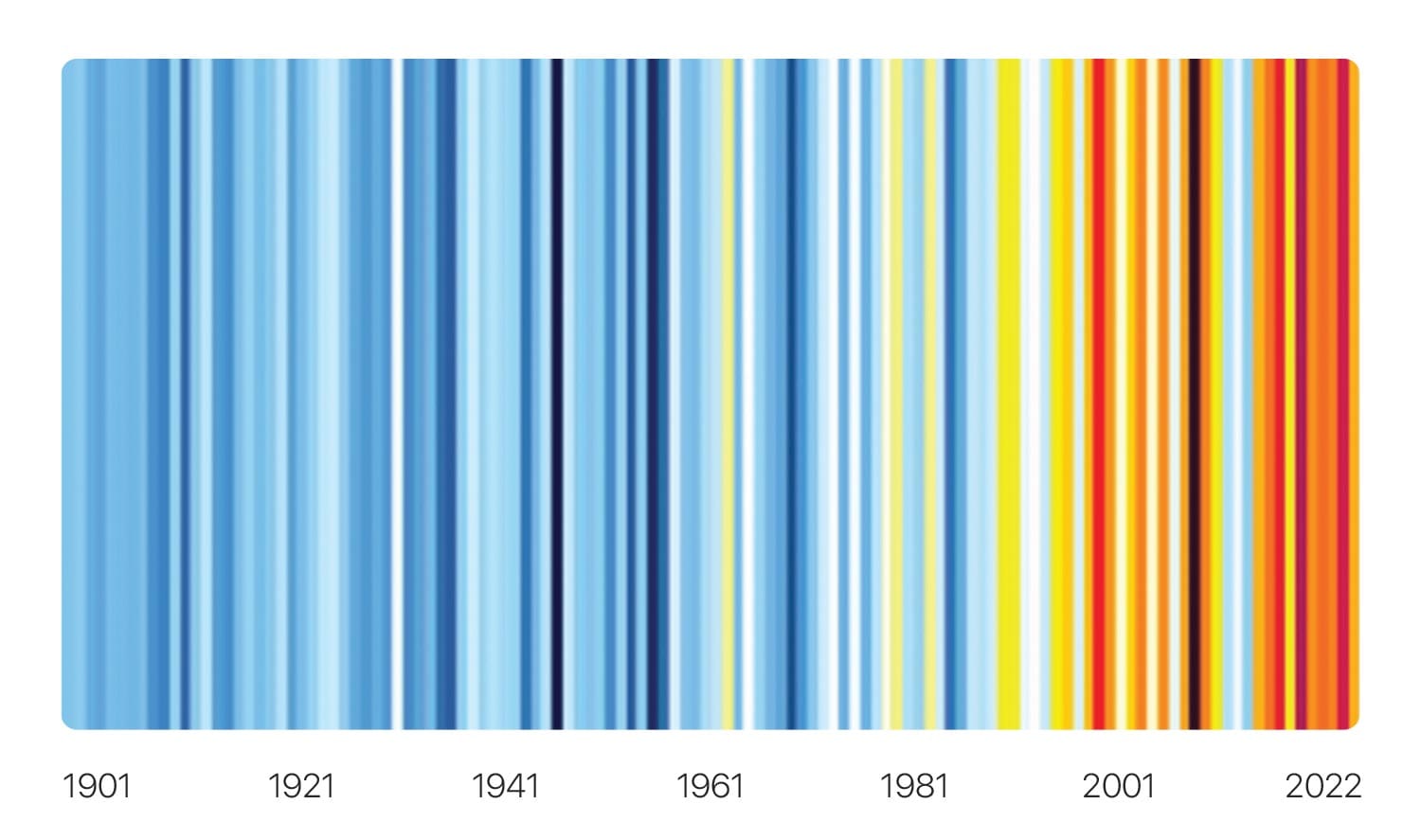

Mongolia is already experiencing the effects of climate change. The country is becoming warmer, with much more volatile rainfall and snow ¬fall patterns. Average surface temperatures in the past decade in Mongolia were 2.3°C higher than they were in 1901–1910, while average maximum and minimum temperatures have increased by the same amount. Because of Mongolia’s latitude and landlocked status, these temperature increases are much higher than the global average (around 1.3°C) and much of the rise in temperatures has happened since 1980. Between 1901–1910 and 2013–2022, average annual precipitation increased from 226 mm to 236 mm, as noted in the World Bank’s 2024 Mongolia Country Climate and Development Report.

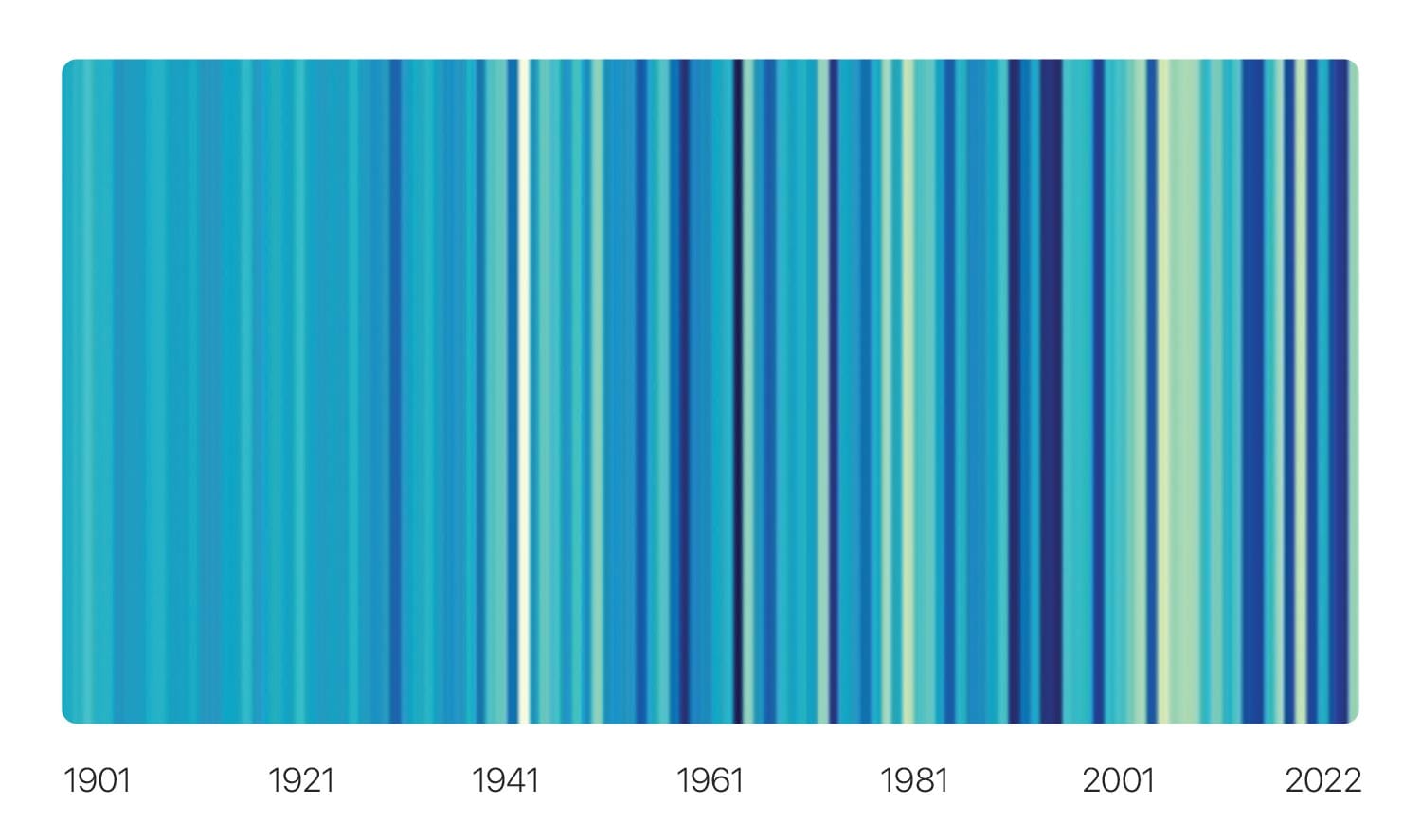

The variability of precipitation has sharply increased over time, with fluctuations growing from 5.8 mm in the first 30 years to 37.4 mm in the last 30 years.

Climate change is expected to increase the frequency and intensity of natural hazards like dzuds and floods. A dzud is a peculiar weather phenomenon unique to Mongolia. It is an emergency related to extreme cold or snow. Since 2000, dzuds have occurred approximately once every five years, but by mid-century, they could happen as often as once every three years. The severity of dzuds will also increase, potentially doubling by 2100, according to World Bank’s projection.

The agriculture sector in Mongolia was severely impacted by the 2024 dzud, similar in scale to the 2009–2010 dzud. By mid-year, 8.1 million livestock, or 12.5% of the national herd, were lost, with nearly half of the breeding stock either dying or miscarrying. This led to a 26.7% contraction in the agriculture sector in the first half of 2024, following an 8.9% decline in 2023, marking two consecutive years of setbacks due to harsh winters.

Temperature and precipitation patterns in Mongolia

Note: In the left-hand pane, blue represents cooler temperatures and orange warmer temperatures over a range of approximately 4°C. In the right-hand pane, darker colors indicate more precipitation over a range of approximately 120 mm.

The Mongolian government is taking policy measures against these.

Mongolia ratified the Paris Climate Agreement in 2016 and released its Third National Communication to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Furthermore, the country has adopted national and sectoral strategies and policies such as National Action Plan on Climate Change (2011-2021), the Green Development Policy (2014-2030), the Intended Nationally Determined Contributions under the Paris Agreement (2015-2030), the State Policy on Renewable Energy (2015-2030), and Mongolia’s Sustainable Development Vision 2030.

At a recent high-level meeting of the 76th session of the UN General Assembly, Khurelsukh Ukhnaa, the President of Mongolia, announced an initiative to plant one billion trees. The implementation of the national “One Billion Trees” initiative was officially started in October 2021. The President also urged other countries to allocate up to 1% of the GDP toward environmental protection.

Successful implementation of the national “One Billion Trees” initiative is expected to improve 4% of the 129 million hectares of land that is currently severely affected by desertification. 7.9% of the country’s territory is currently covered by forests and the national objective aims at increasing this indicator to 9% by 2030. Moreover, the action is expected to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 600,000 tonnes, according to early estimates. The “One Billion Trees” national movement will be rolled out in three phases over the next decade: preparation, intensification, and maintenance.

Recent years have seen rapid urbanization, with more than 50% of the country’s population living in Ulaanbaatar. This transition in lifestyles and livelihoods has presented many challenges including unplanned settlements and air, water, and soil pollution.

A UNICEF study estimated the lost opportunity cost caused by air pollution in Mongolia’s economy over the last 5 years at US$1.4 million. Generations of Mongolian Governments have made attempts to reduce air and environmental pollution, although they have been mostly ineffective.

A marked improvement in air quality in the city was noticed after the government implemented a ban on raw coal in Ulaanbaatar, instead encouraging the usage of refined coal briquettes in 2019.

However, the air quality indicator continued to deteriorate rapidly since 2021, remaining one of the biggest challenges for the capital city of Mongolia.